Your Voice Matters: Speaking Up About Suicide

As National Suicide Prevention month comes to a close, I’ve been reflecting on what OUR responsibilities are as family, friends, or colleagues to people who are plagued with suicidal thoughts. In my own practice, both with my clients and as a source of support to my friends and family, what is my role when it comes to the topic of suicide?

All of us have been touched by suicide, yet the subject remains taboo. There is deep shame and stigma attached to suicide, often because when someone completes the act, their loved ones blame themselves, thinking that they should have done something to stop it. If this speaks to you, then I hope it also comforts you to know that there are usually many complex conditions going on within a person's head that lead up to suicide, and it is difficult to pinpoint any single act or individual who could have thwarted the act.

“People who attempt or complete suicide, want to escape the pain of life; they do not want to die. ”

Most people who complete suicide struggle with mental illness like depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance abuse. Suicide and related behaviors like ideation, or talking about taking one’s own life, are ways to cope with and manage deep pain and suffering. People who attempt or complete suicide wish to escape the pain of life; they do not want to die. This is an important distinction, especially if you feel anger toward the person who ended or attempted to end their life. If you believe you are partly responsible, you must consider that whatever your actions or words were, or lack thereof, they were only just words or actions, and not the source of depression and mental suffering that lead to suicide. The same is true for inaction. It is impossible to know exactly what may been different, but its unrealistic that the person's pain and suffering could have been relieved by any one act.

If you have reason to believe you were blamed, consider the dark and isolated place the person was in at time they completed suicide. The thoughts of a suicidal person are often deeply distorted at the time the act is attempted, and not a reflection of reality. This self-blame is likely an illusion that you are creating for yourself, irrationally rooted in the false assumption that you had more control over the situation than you actually had. Self-blame interferes with grief and prolongs healing. The first step is acceptance of the suicide and that you did not have control over it. Then the healing can begin.

Although there are many things you can do to decrease the chances of suicide, it is also a societal problem and a large scale public health concern, and the burden does not fall entirely on your shoulders . We do not live in a black and white world, it is a world of grey and there are no absolutes. Learning to recognize warning signs, risks, and how to handle situations when you suspect someone is contemplating suicide can be empowering and help you realize how influential you can be. Suicide prevention is our collective burden to bear, as highlighted in this Huffington Post article. Unfortunately, suicide prevention funding efforts don’t match those of other leading causes of death because the stigma around suicide is difficult for many to overcome. This point is painfully obvious when we look at this recent New York Time's article. The article calls to attention how woefully inept we are at addressing the suicide epidemic enshrouding our nation’s veterans. For effective prevention, we need to mobilize on a higher level.

Recognize the Warning Signs

Your loved one is:

- Talking about death, wanting to die, or expressing morbid thoughts. Think of this as a cry for help. Most suicidal people seek medical services and professional help prior to attempts. Remember that they don’t want to die, rather they want to end their pain and suffering.

- Settling affairs: Making a will, giving away possessions.

- Saying goodbye.

- Withdrawing or socially isolating themselves.

- Engaging in self-destructive behavior, such as increased alcohol use, reckless driving, or acting recklessly, as if they had a death wish.

- Seeking out items that could be used in an attempted suicide, like weapons or drugs.

- Changed appearance, lack of self-care.

- Mood swings.

Recognize the Risk Factors

Is your loved one at-risk?

- Mental illness- Depression, schizophrenia, PTSD, and bipolar disorder are all big factors in suicide; 90% of people who take their lives have a diagnosable mental illness.

- Hopelessness-The majority of people who are suicidal don’t trust in their ability to cope with their conditions. Signs of hopelessness might bestatements about a bleak future or having nothing to look forward to.

- Loneliness or social withdrawal.

- Terminal illness or chronic pain.

- Substance abuse.

- A recent loss or a stressful event such as the loss of a spouse, especially in elderly adults.

- A History of trauma and abuse. A recent study found that the higher number of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES), the greater the chances were of a suicide attempt.

- Feelings or statements of worthlessness such as “I’m such a burden” or “everyone is better off without me”.

- Prior suicide attempts.

- Inability to identify something to live for.

- Identifying as LGBT and not having a supportive household.

The more risk factors are involved, the higher the risk is of a potential suicide attempt.

The statistics

Gender – Males are of higher risk of death by suicide. Males die at four times the rate of women and use more lethal means such as firearms. Women, however, attempt suicide at three times the rate of men but use less lethal means , such as self-poisoning.

Means – Access to firearms is the biggest risk factor. Firearms account for half of all deaths by suicide.

Age – The highest risk age demographic is over 45.

Race – The highest risk race is White, followed by American Indians and Alaskan Natives. In 2013, White males accounted for 70% of deaths by suicide.

Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the U.S and the third leading cause of death for youth. Statistical Sources: the AFSP and the CDC

What do I do if I think a loved one is suicidal?

1. Talk about it.

There is a dangerous misconception that by vocalizing your suspicion, you can put the idea of suicide into someone’s mind. This is not true, and in fact, will likely help the person feel validated and offer them a chance to talk about their otherwise pent-up negative feelings. You may not feel like you are doing much to help, but by lending a listening ear, and asking open-ended questions about how they are feeling, you are doing the most important and powerful thing you can do to prevent a suicide.

Conversation starters – Verbalize what you notice is different about them and tell them you care. Some examples of what to say are, “I’ve noticed you’re not like yourself lately" or "I’m concerned about you. How are you?”

Asking directly – It is important to approach the situation rationally and ask the person direct questions. You might pose the question in a way that will encourage an honest answer. For example, you can ask, “Have you had thoughts of wanting to die?”, or, “Have you thought about killing yourself?”

Supportive statements – Say things that convey warmth and empathy, such as “I may not understand what you are feeling, but I am here for you,” “you are not alone,” and “I understand what you feel is intense, and you may not believe it now, but you will feel better in time as this will pass.” Let them know what they mean to you and why they are important to you.

Behavior to Avoid – Do not show shock, surprise, anger, and do not lecture or argue with the person.

2. Assess the Level of Risk

- Low – Suicidal thoughts, but without any plan. Verbalizes things to keep living for.

- Moderate – Suicidal thoughts with a vague plan that is not lethal, or no access to the means indicated for carrying out the suicide.

- High – Suicidal thoughts with a specific plan that is highly lethal with access to the means to accomplish it. The person claims they will not suicide.

- Severe – Suicidal thoughts with a specific plan that is highly lethal with access to means to accomplish it. The person claims they WILL suicide.

The questions to ask to assess risk are as follows:

- Do you have a suicidal plan? (PLAN)

- Do you have means to carry out your plan? (MEANS)

- Do you know when you would do it? (TIME SET)

- Do you intend to suicide? (INTENTION)

3. Planning for safety

If the risk is high, gently plan with the person to remove any means of suicide for their safety. For example, if their plan is to take a giant container of Tylenol washed down with a liter of vodka, then ask if you can remove the Tylenol to “keep for their safety during this tough time.” Do this in a loving way that shows care and concern, without contributing to more feelings of humiliation or shame.

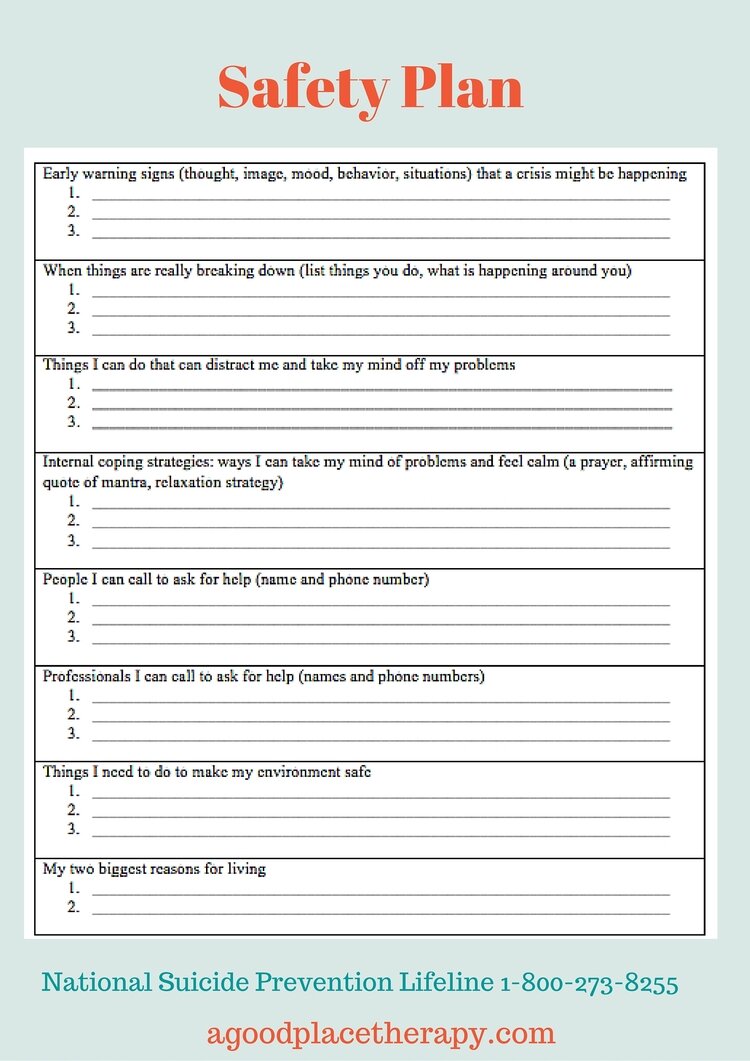

Sit down with your loved one to create a written safety plan. Though it may feel like the suicidal feelings will last forever to the person, suicidal thoughts will pass in time and only rarely do they persist. You can encourage your loved one to make a plan that they can refer to that will help them through the dark times, and support them as they write it down.

A Safety Plan

An example of a safety plan. To download as a PDF, click here

- What are my warning signs? Are there thoughts, images, moods, behaviors, and situations that encourage suicidal thinking?

- What can I do to distract myself from negative thoughts?

- What are ways I can internally cope, such as a prayer, an affirming quote, or a mantra? Implement a relaxation strategy.

- Who are the people I can call to ask for help? Make a list of their names and phone numbers, which may include, friends, family, or even clergy.

- Who are the professionals I can call to ask for help? Make a list of their names and phone numbers.

- What do I need to do to make my environment safe?

- What are my reasons for living?

The number to the Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-TALK (8255), should also be included in the plan. Also, get a verbal commitment from the person that they will follow through with the safety plan and seek help from a professional before attempting suicide. Click here For a downloadable Safety Plan PDF.

4. Connecting to the right supports

“Eighty to ninety percent of people experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts get better through treatment using talk therapy and medication.”

Therapy: There is hope. Eighty to ninety percent of people experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts get better through treatment using talk therapy and medication. People with suicidal thinking, who have attempted suicide, or are experiencing depression should see a psychiatrist for psychotropic medication assessment in addition to a licensed psychotherapist. The treatment modalities of DBT (Dialectical Behavioral Therapy) and CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) are particularly helpful. Both DBT and CBT can help depressed and suicidal people find hope and meaning in their lives and learn ways change distorted thoughts about themselves, the world, and others. They are also very effective therapies for dealing with stress. You can find a therapist by searching the listings of providers covered by the person at risk person's insurance, or by looking online at the "Psychology Today" website, which lists providers by zip code and specialty. If your loved one has begun a course of anti-depressants for the first time, be sure to be especially mindful, as sometime suicidal ideation can briefly increase in the beginning of anti-depressant treatment, especially in adolescents.

Connectedness: Reducing isolation and ensuring strong connections between friends, family, community, and important institutions can make a big difference. It may be helpful for your loved one to attend a support group, NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) chapters nationwide offer different types of support groups, including social groups on the weekends. The website "Meet Up" offers groups anyone can join based on shared mutual interests.

Continue to be there: Provide support to your loved one through the long haul. Continue to let them know how much you care about them and value their life. Encourage them to follow through with treatment options and take medication. Join them in healthy activities such as exercising together and preparing healthy meals. Remember that if your loved one is depressed, they may isolate themselves. Do not wait for them to reply to your text message or return your phone call. The normal rules of reciprocity don’t apply. Be persistent.

If the person you are concerned about is a co-worker, you can still play a role in helping. You are often in a position to observe and notice changes and spend a great deal of time with your coworkers. By fostering a sense of community and belonging in the workplace, you can provide emotional support. Contact HR or your workplace EAP for advice or resources.

5. Helping through Crisis

If you determine your loved one is high risk, then you can take actions to help keep them safe. If you can, meet them and escort them to the nearest psychiatric emergency room and wait with them. If it's not possible for you to go with them, help them identify who can go with them. Ensure that transportation is coordinated and you have a commitment from them to go. If this is also not possible, then call the local police department or 911 and be prepared to answer questions with the key information.

There is always hope

You are not alone. The work you need to do to support your loved one takes courage and can be a very isolating experience for both of you. As a society, we need to do better. Efforts such as this Zero Suicide Initiative shows promise of strengthening and integrating our systems of care, including healthcare, hospitals, emergency response systems, schools, workplaces, and law enforcement. They are also making a concerted effort to increase mental health parity at the legislative level. Please lend organizations like Zero Suicide Initiative your support, and please don't wait to reach out to any friends, family, or colleagues you feel may be at risk.

For more information and resources:

American Association on Suicidology

Kerrie Thompson is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in private practice in NYC. To work with her, contact her here.